It is not a coincidence that the same people who have an incorrect position on the National question almost always also end up having an incorrect view of the Labor question as well, and vice versa. For example, it was the same false “leaders” who betrayed the 1928 and 1930 Comintern resolutions on the Black National Question who also liquidated the Trade Union Unity League and the CPUSA’s brief revolutionary position on the Labor question during the Third Period. That is because at their core these are one and the same: they are betrayals which are products of the ideas and practice of exploiters and oppressors rather than of the workers. They represent a failure to chart a course that answers the burning questions of our society posed by concrete material conditions, from the perspective of socialist revolution.

Both the Labor and National question are questions posed to revolutionaries by their concrete national conditions and context. They cannot be understood outside of those parameters. They are thus also bound up with one another in a US context, as the economic and political struggles of the multinational US working class are by definition inseparable from the struggle between the American oppressor nation and its various oppressed nations and national minorities. This Black August it is worth reflecting on a few sequences in the history of our movement which demonstrate this truth, that the Black National Question, and the struggles of other colonies and semi-colonies of American imperialism in the US, are intimately bound up with the Labor Question as part of the set of concrete problems posed to us on the road to socialist revolution in the United States.

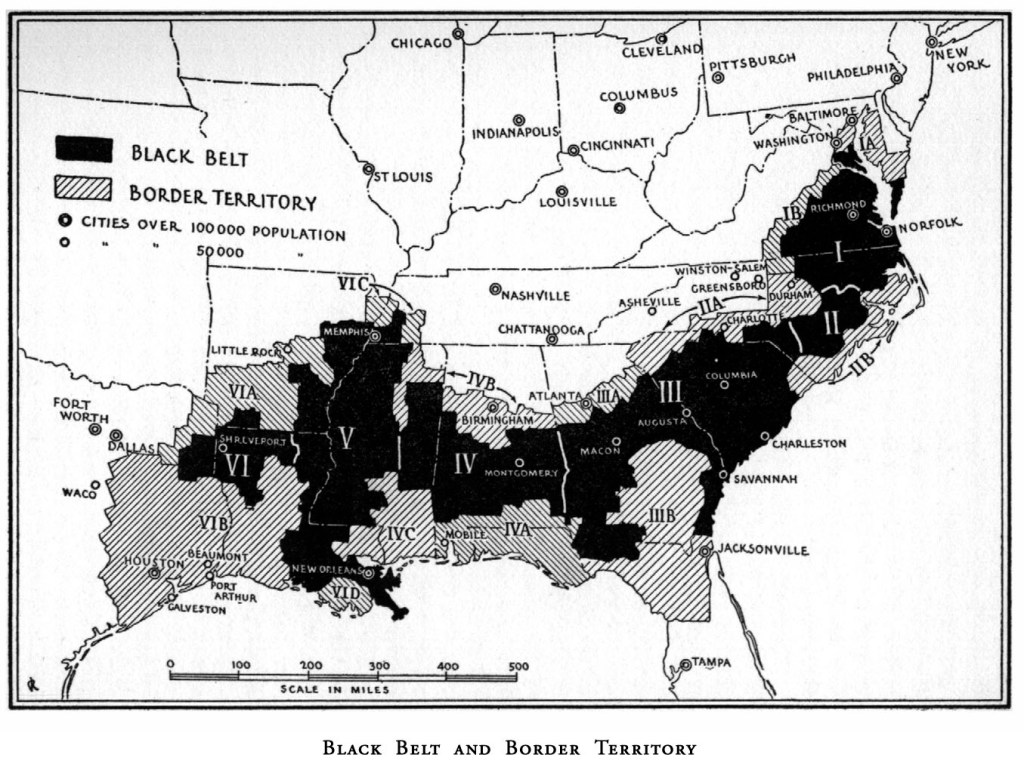

One of the most well known examples of this convergence is the Alabama Sharecroppers Union, even if the lessons of that struggle are still not well understood. The Sharecroppers Union, founded in 1931, was a product of the Comintern’s Third Period policies in the United States. In particular, the Third Period turn meant two key shifts in the mass work of the Communist Party (USA): 1) the recognition of the Black population in the US South (the “Black Belt”) as an oppressed nation with the right to self-determination (meaning the right to form an independent state), and 2) the pivot to creating an independent class-conscious union center that would serve as the revolutionary movement’s main axis for work in the labor movement, in contrast to the prior policy of “boring from within” the chauvinist and reactionary American Federation of Labor (AFL).

These twin pivots created a convergence of revolutionary policy that resulted in the formation of integrated and majority Black membership independent mass organizations in the US South. The Alabama Sharecroppers Union was one of those organizations. It was created by the just and correct left turn the Third Period marked in the US, and by that same token it was liquidated when the policies of the following Popular Front period were misapplied in the United States by arch-revisionists Earl Browder and William Z. Foster to enact a rapid rightward over-correction to the Third Period’s leftward turn. The Sharecroppers Union creatively combined the Black Belt Thesis and the calls of the new Trade Union Unity League to mobilize and lead tens of thousands of deeply impoverished tenant farmers (referred to as “sharecroppers” because as semi-peasants they did not own the land or tools they worked and had to give a majority share of their crop to large landowners). The struggles of the sharecroppers against the large landowners, and the sharecroppers themselves, were the direct descendents of the struggle of the enslaved Black masses against the Southern plantation owners. It was a struggle that linked the policies of land to the tiller and independent workers organizations effectively, constructing the largest, most active, and most militant organization the CPUSA ever created, or would create, in the US South.

For this vital work the revolutionaries and masses who lead the SCU were rewarded with betrayal by the CPUSA top leadership. When the CPUSA applied the Popular Front policy to embrace an alliance with the segregationist Democratic Party, militant class organizations of the Black toiling masses like the SCU became inconvenient. A couple years after the TUUL was liquidated by Browder into Lewis’ CIO, the SCU was liquidated first into a string of business unions leading eventually to the United Cannery Agricultural Packers Allied Workers of America.

Three decades later, independent revolutionary organizations of Black auto workers, the “Revolutionary Union Movements”, went through a similar trajectory. Mass organizations of militant and class-conscious Black workers burst onto the scene combining leadership in the struggle for daily economic grievances and leadership in the struggle against national oppression to great effect. Then, through a combination of inevitable practical challenges, external repression, and, most importantly, leaders who put incorrect lines in command, the Revolutionary Union Movements and their successors had all essentially folded by the mid-to-late of the 70s. In particular, their efforts had been liquidated into “caucus”-type labor organizations, or split through conflicts between different cliques in upper leadership, dooming them to failure despite their initial success.

These and other heavy episodes from the history of our movement show us how and why the National and Labor Questions are inseparable on the road to socialist revolution in the world’s main imperialist power. History is our greatest teacher, it represents to us as Marxists the blood and sweat spilled in attempt to make the destiny of the final class in history reality: a classless society free from exploitation and oppression. Its lessons, won through hard struggle, must be understood if we are too march forward and go farther than those that did before us.

It is thus the task of all comrades to, in the course of their organizing and practice, study and understand this history. As we ourselves take the first long steps down the path of class-conscious, militant, and independent labor organizing, we must meet the challenges those who came before us met, such as the challenge of combining correct positions on the National and Labor Questions to lead among the workers and laborers of the Black Nation, and other oppressed nations and national minorities within the territory of the United States, in the same explosive and powerful way as before. However, this time around we must be far-sighted, and from the first day understand the lesson that everything flows from a correct political line, including a correct organizational implementation of that line. Our history teaches us that internal deficiencies and errors are primary in our setbacks and failures as revolutionaries, and our work in the national liberation movement and/or the labor movement is no exception.

Let us as revolutionaries unfold a new wave of work in these sectors in the coming years, and in doing so struggle through, in theory and practice, the problem of organizing the masses of nationally oppressed workers in the US, the problem of the role of the trade unions and labor work in the fight against national oppression, and other burning questions.

Primary Sources:

Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communist During the Great Depression

Red Harvest: The Communist Party and American Farmers