As part of New Labor Press’s goal of highlighting and educating revolutionary workers and sympathetic activists on the history of our class’ struggles, and in honor of International Working Women’s Day, we wanted to share with you all a brief overview and summary of the incredibly important, but now almost totally forgotten, history of the red and revolutionary needle trade workers.

For those that don’t know, “needle trades worker” was an umbrella term used in the labor movement to refer to all workers in the various different clothing and garment trades. Although composed of both men and women, in the garment industry women made up the majority of workers, and in no other sectors did women play a larger organizing role than in the textile, garment, and clothing industries. While the struggle of the militant class conscious textile workers is worthy of its own article, we wanted to highlight the history of the revolutionary needle trades workers in the 1920s and 1930s in particular because of the pioneering work they did putting into practice the communist method and principle of industrial unionism, work which we must all look to and learn from given the conditions of the modern US imperialist economy.

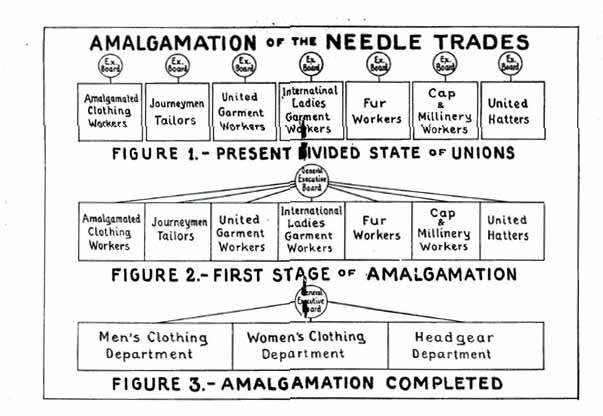

Due to realities of the industry, as well as deliberate policies of division by the employers, the garment and clothing industry was divided up on the shop level like almost no other at the time. Rather than being organized into factories of thousands, or even tens of thousands, of workers, the garment industry was divided up into thousands of small individual shops which were further divided up by what type of materials they workers with and clothing they made. There was the divide between men’s and women’s clothing shops, hat shops, fur workers shops, leather shops, divides among immigrant and native worker shops, separate discriminatory wage scales for Black workers, etc.

These divides created two basic policies that could be pursued by trade unions in the needle trades: 1) the reactionary policy of the AFL business unions to accept the capitalists’ various divisions of the workers and try and win control over the workers by cutting deals and collaborating with the capitalists or 2) the revolutionary policy of the Left-wing needle workers that rejected these divisions and attempted to organize workers on the basis of industry-wide unity and an organized struggle against the gender, race and national chauvinisms that helped enforce these divides.

Spurred on by the expulsion of the large combative left-wing from the AFL-affiliated International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), even prior to the Comintern’s correct condemnation of the boring-from-within policy and the formation of the independent red Trade Union Unity League by the CPUSA, progressives and Communists in the ILGWU began work to form a new independent, class-conscious, combative, and industrial union. In alliance with the left-wing men’s clothing workers, furriers, hatters and other needle workers, in 1928 they formed the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union (NTWIU).

While still doing work by departments (including departments specifically devoted to building up the leadership and participation of women, youth, and Black workers in the needle trades), by thoroughly theoretically embracing and practically implementing the principle of industrial unionism the NTWIU literally broke down the divisions imposed on them by the bourgeoisie. Lead by leaders such as Rose Wortis, the NTWIU was consistently the largest of the TUUL’s constituent unions, and pioneered the use of the strike weapon across artificially divided shops and companies, regularly leading dozens or even a hundred shops at a time to simultaneously strike in order to win industry-wide demands. For example, in July 1931 the NTWIU lead a successful strike of around 336 different fur and leather shops that tripled ($5 to $15) the wages of workers in the striking shops and on the coattails of that strike helped organize a similarly large and successful industrial strike of dressmakers.

The history of the NTWIU and revolutionary needle workers destroys the idea that forming an explicitly red, class-conscious, combative industrial union in the US will always be an inherently “sectarian” project condemned to perpetual isolation and obscurity among the broader working class. Not only was the NTWIU more combative and politically conscious, it challenged and outgrew the AFL business unions and locals of the time in industries like the fur trade, and especially in the then heart of the US garment industry, New York City. It consistently lead successful industrial actions, successfully based itself in some of the most exploited and oppressed workers in the entire country, and was only dissolved as a result of the broader rightist ideological-political errors that came with the CPUSA’s incorrect implementation of the Popular Front line which eventually lead to the liquidation of the Party itself in the 1940s.

In the context of our contemporary imperialist economy where so many of the large factories/enterprises of the 20th centuries have been split up into a thousand smaller shell companies, locations and shop, we have so much to learn from the needle trades workers of this period. In particular, we must embrace the principles of helping establish proletarian unity through an organized struggle against chauvinism and reactionary ideas within the working class itself, rather than ignoring or papering over such reactionary trends prevalent among sections of the workers. While they still had their own self-admitted failures in their work among women, youth and Black workers (the NTWIU never felt there was sufficient participation of these groups in union leadership for their standards), the needle workers still overcame a thousand barriers to unite as an industry, as a class, in a way that did not exclude or erase, but actually centered and was based on the leadership of women, immigrant and nationally oppressed workers and the struggle against gender, race, and national chauvinism. Beyond simple participation and “bravery”, Rose Wortis wrote for the Communist Party’s publication devoted specifically to the struggle of proletarian women (The Working Woman) that during NTWIU dressmakers strikes:

“The women dressmakers did not merely distinguish themselves for bravery on the picket line. The women dressmakers, as the advance section of the women workers, took an active part in the strike leadership. They helped to formulate the policies of the Union and participated in great numbers on the General Strike Committee, the Executive Board of the General Strike Committee, on the various Sub-Committees, were hall chairmen and hall secretaries and were found generally capable and efficient, thus proving more clearly than any amount of propaganda that the women workers once they are awakened to their responsibilities to their fellow workers can fight as well as men for the interests of their class.“

We have a lot to learn from our history, and even more to uncover. For example, how many of us have even heard of the Needle Trades Workers Industrial Union, one of the most successful, politically-advanced, and largest revolutionary labor unions in US history, before reading this article?

So much of this rich and important history of our class has been systematically destroyed and hidden, quite literally considering how much primary material from this era has been transformed into private property and buried deep within obscure archival libraries in the nation’s largest private bourgeois universities. Even in doing the research for this article we feel we are just barely scratching the surface of this one story among thousands of the last hundreds of years of struggle against US imperialism and its state. We hope to do more articles like this in the future, and hope these articles spur curiosity in our readers to go out and learn the history of the revolutionary working class as it relates to their industry, their lives, and their organizing.